Embodied Agents using a Turtlebot3

Understanding embodied agents with a Turtlebot3 and ROS.

This work was done in collaboration with Liyah Coleman at the Mechatronics, Controls, and Robotics Lab at New York University Tandon School of Engineering. The code for this project can be found here.

Introduction

In 2024, embodied agents have become incredibly popular. Large language models (LLMs) are now considered trustworthy enough (or so we think) to be given physical forms, and many companies are taking the next step in AI by deploying these agents in the real world. In this post, we will explore how to create an embodied agent using a Turtlebot3 Burger robot (henceforth referred to as ‘the robot’) and ROS. Specifically, we will create a simple embodied agent that can navigate a grid. To say that using an LLM to navigate a grid is overkill would be a massive understatement, but this will serve as a good starting point for understanding how to create embodied agents.

System overview

Our goal is to set up a system where we can ask the LLM to chart a course for the robot to reach a goal position, given the robot’s current position. The LLM will send a set of instructions to the robot, which the robot can understand and execute. The robot will then carry out these instructions to move to the goal position.

Since the robot we are using is a differential drive robot (it can move straight and turn), we can simplify the problem by reducing the number of actions the robot can take. The robot can step forward, turn left, or turn right. In this experiment, we are not using any of its sensors, so the robot is essentially blind. The shortcomings and future improvements of this system will be discussed later.

Preparing the robot

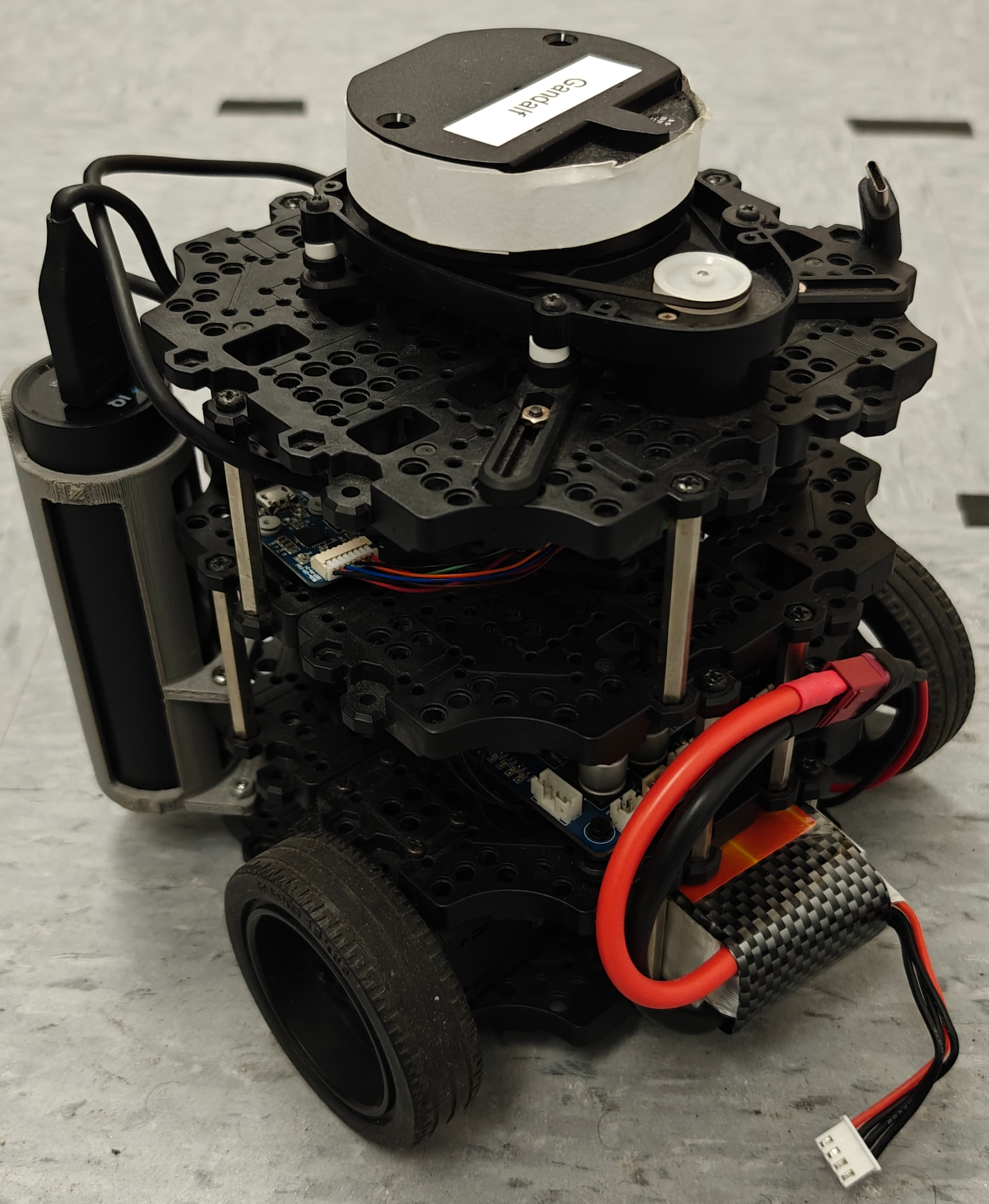

First, we installed ROS Humble on the Raspberry Pi 4 onboard the robot. Then, we installed the Turtlebot3 ROS packages so that we could control the robot using ROS. Finally, we created a simple ROS package that allows the robot to receive instructions from the LLM and move accordingly. There are several ways this problem can be approached, but we chose to use a simple publisher-subscriber model since this is not the focus of the project. Figure 1 shows the Turtlebot3 Burger used in the project.

Figure 1: Turtlebot3 Burger.

Once this setup was complete, we were able to send an array of instructions to the robot and watch it move accordingly. For example, if the robot starts at \(\left(0,0\right)\) facing north, and we send the instructions ['step forward', 'turn right', 'step forward'], the robot will move to \(\left(1,1\right)\) facing east. With this setup, we are basically done with the robot side of things.

Using the LLM

In this section, I will focus solely on the approach that was successful for us. For a comprehensive discussion of all the other methods we explored, please refer to the accompanying blog post.

We selected the Llama-3.1-70B model for our experiment. This choice was primarily due to its open-source nature and because it is the smallest model in the Llama family that was compatible with our prompt requirements. We utilized the model in its default configuration, without any fine-tuning.

To implement this, we created a Hugging Face space that uses Gradio to build a straightforward web interface, allowing us to input the robot’s current position and desired goal position. While we initially used this web interface for testing purposes, we eventually developed a Python script to facilitate message exchanges with the Hugging Face space. The system prompt we provided to the LLM was as follows:

Click to see the system prompt

You are controlling a 2 DOF robot on a 50x50 grid. The robot can move one step in any of the four cardinal directions. The robot can perform the following actions:

- - 'up': Move one unit up (increasing y coordinate by 1).

- - 'down': Move one unit down (decreasing y coordinate by 1).

- - 'left': Move one unit left (decreasing x coordinate by 1).

- - 'right': Move one unit right (increasing x coordinate by 1).

Given a target coordinate, your task is to calculate and output the shortest sequence of commands that will move the robot from its current position to the target position.

Output Format:- - Begin with the exact phrase: 'The full list is:'.

- - Provide the sequence of commands as a JSON array, with each command as a string. Commands must be exactly 'up', 'down', 'left', or 'right'.

- - All coordinates should be formatted as JSON objects with keys 'x' and 'y' and integer values. For example, the starting position should be output as {'x': 0, 'y': 0}.

- - When calling tools, ensure that all arguments use this JSON object format for coordinates, with keys 'x' and 'y'.

- - Example of correct output: If the target coordinate is {'x': 2, 'y': 3}, your response should include: 'The full list is: ["right", "right", "up", "up", "up"]'

Please ensure that all output strictly adheres to these formats. If any output is not in the correct format, redo the task and correct the output before providing the final answer.

A detailed system prompt is essential to ensure the LLM understands exactly what is expected. It’s important to note that the system prompt instructs the LLM to provide movement directions without considering the robot’s current orientation, resulting in instructions like up, down, left, or right. In contrast, the user prompt we used was much simpler:

The robot is at 'start_position': {'x': 25, 'y': 24}. What is the shortest list of actions to take in sequence to get to 'target_position': {'x': 27, 'y': 25}?

Sending both the system and user prompts to the LLM yielded the following response (Note: In this example, the robot was oriented facing south):

Model Response: [["The robot is at 'start_position': {'x': 25, 'y': 24}. What is the shortest list of actions to take in sequence to get to 'target_position': {'x': 27, 'y': 25}?". 'The full list is: ["right", "right", "up"].']]

A function was written to parse the response and send the instructions to the robot. Depending on the robot’s current orientation, the response was translated into commands that the robot can understand, such as (step forward, turn left, or turn right), and then sent to the robot. These commands were then transmitted to the robot. Since the robot continuously listens for incoming instructions, it executes them in sequence as soon as they are received.

Results, Limitations, and Future Work

The system performed perfectly in all the test cases we tried. The robot successfully moved to the target position in the shortest number of steps. The LLM effectively understood the user prompt and provided accurate instructions, which the robot correctly interpreted and followed.

However, there are several limitations to this system. Since the robot operates in an open-loop manner, it essentially navigates “blind” due to a lack of sensory feedback. It only knows its initial direction because we provide it, and it can determine its final direction after executing the instructions. The robot’s movements are hardcoded, so a 90° turn isn’t always precisely 90°, leading to cumulative errors over time. Additionally, the robot can only move in discrete unit steps, so it cannot travel diagonally. This limitation means that when the goal positions are farther away and require multiple turns, the robot may end up with a significant positional error. Furthermore, the robot lacks obstacle detection and will continue moving even if something is in its path. Lastly, the LLM used is quite large, and I’m confident that a much smaller model, with some fine-tuning, could handle this task just as effectively.

In the future, I plan to incorporate feedback from the robot’s sensors. This enhancement would allow the robot to navigate more accurately and reduce the error between its final and target positions. Additionally, I intend to fine-tune a smaller model, such as the Llama-3.1-8B, to evaluate if it can perform on par with or even better than the Llama-3.1-70B model.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: